Reforming the presentation of conference proceedings: a plea to end the madness

A blog by Chris Cooper and Zahra Premji (cite via: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.18593615)

If you ever tried to describe the process of finding conference proceedings, people would think you’d lost it. Which would be fair. We’re told to include them - that’s the guidance (1). But finding them is plainly crazy. Not to find them would be the rational thing to do, of course, - only, it isn’t, because then you’d miss things, and people would think you were crazy too.

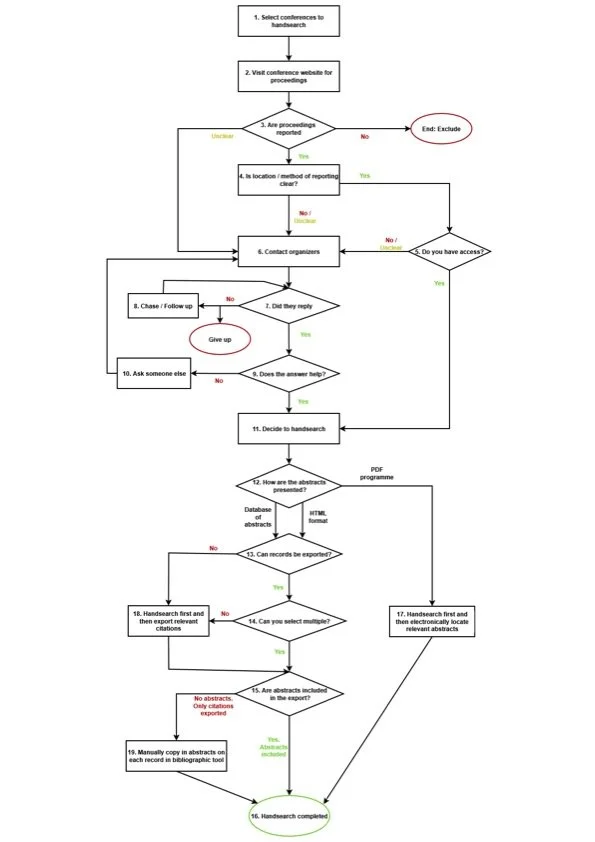

The trouble isn’t the conferences themselves; it’s the architecture of how they are reported (2). The result, as we illustrate in Figure 1, is a process which is quietly maddening.

Figure 1: The quietly maddening process to identify, search, and export conference material

We think it can be simpler. After all, if you’re going to host a brilliant conference, surely the least you can do is make sure people can actually find the proceedings afterwards. Otherwise, what’s the point?

We set out three linked proposals on how the process of reporting conference proceedings should change. Our aim is to improve the accessibility of conference proceedings and therefore the ease of handsearching to inform evidence synthesis.

Our target audiences here are: i) anyone putting on a conference, ii) organising the presentation of conference material, or iii) attending a conference (because you want your work found and used, right?)

First: what is handsearching?

To be clear, we are talking about handsearching conferences. Defined in the Cochrane Handbook as: ‘a manual page-by-page examination of the entire contents of a journal issue or conference proceedings to identify all eligible reports of trials’ (1).

We know there are ‘other ways’ to identify conference proceedings and abstracts beyond handsearching, such as scraping the data from websites, but this is variously legal or illegal depending on the website in question. There are, we note informally (from trying the legal ways, you understand), various imperfections to engage with too. Also, conference abstracts can be identified by searching Embase or CPCI-S, but we know too that reporting is patchy and incomplete, so these searches are incomparable to a handsearch (2) (which focuses on the full report). So, now, on to the proposals.

Proposal 1. Signposting: clearly signposting where (or if) proceedings are reported

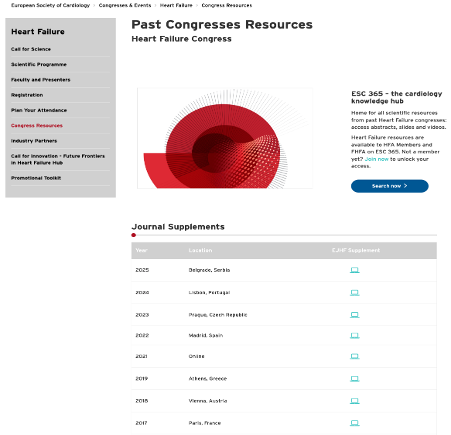

See Figure 2: the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). This should be the literal inspiration to all, since in our view, it’s the prevailing gold-standard on how to report if - and where - proceedings are reported. Admire: we have a perfectly clear statement of what proceedings are available and where they are to be found. Also, working links to the on-line and searchable interface (3).

Figure 2: The ESC website reporting their conferences and links to reports

The point here is efficiency: simply, we want to know, in an instant, that proceedings are reported and where they are accessed. So we can get to Proposal #2 calmy and confidently.

Other points:

o A clear statement of where (or if) proceedings are available should be reported on the conference website AND organisation homepage;

o If a conference is planned but cancelled, this should be reported alongside the conferences that did take place;

o If a conference happens occasionally, or bi-yearly, this should be clearly stated, so users are not hunting down proceedings which do not exist;

o Links to proceedings should be checked regularly to ensure they work; and

o A clear point of contact should be reported.

Proposal 2. free access: make all proceedings freely accessible

Conference proceedings are often freely available but the way in which users have access to them varies. The various forms mentioned below may be hosted on the organisation or conference website, or as part of a journal, often a supplement issue. Examples here, in order of ease, and therefore of preference:

2.1 Accessing via Databases

The ISPOR presentations database (https://www.ispor.org/heor-resources/presentations-database/search) is a quietly persuasive example of near-perfect accessibility: a single gateway, offering a free and searchable resource, which lists all conference presentations at ISPOR (often including a PDF of posters) (4). As it relates to accessibility, this is an excellent example in its class.

2.2 PDF Abstract books

Now, the ISPOR database is, obviously, a costly resource, sustained by membership subscriptions rather than goodwill. PDFs of proceedings - for example, abstract books - should be easily accessible as an imperfect minimum. The filename structure should be clear to which conference the abstract book relates (as journals often report more than one conference with the quiet confidence that readers can tell the difference between subtle deviations in cover detail).

2.3 HTML Reports

Many journals now offer an HTML-based structure which, in principle, is good for access but, in practice, is rather less obliging when it comes to handsearching (e.g., ASH (5)). We tend to regard it as the worst of the available options: a kind of navigational phantasmagoria involving endless dropdowns and the constant low-level anxiety of losing one’s place. Still, in the literal absence of anything worse - which, to be fair, is nothing at all - we will take it.

Other points:

· Free access though, is really our point here. There’s a sort of backwards economy: the more freely available and accessible the work, the more attention it should attract - for the delegates and the conference.

Proposal 3. Identifying, selecting and exporting conference content

Now the struggle. In Table 1 (below) we describe two examples of the process of handsearching and exporting abstracts, from ASH and, separately, ISTH. Both tedious experiences in their own awful way, inexcusable, and not experiences in the minority. Taking ASH as an example: ASH is a HUGE conference and its experience for handsearching is disappointing and labour intensive (we have raised this before, elsewhere (2)).

Our aim/point here is to reduce the steps a searcher should take to identify, access, and export abstracts. A few clean steps. Not an obstacle course. The following improvements would reduce and minimise the number of steps needed to handsearch and we consider them simple to introduce:

1. The ability to see - in the same field of vision - the title and abstract (this can be as with PubMed a toggle switch that can turn on or off). We don’t want to click through to view the abstract – we want to see it, alongside the title, and move on;

2. The ability to select multiple abstracts and then export them ALL at the end of the handsearch. As one does when working in PubMed Not one, by one, by one, by one…; and

3. Ensuring that the citation detail AND abstract passes when data are exported. We want to avoid having to copy and paste abstract detail.

Again, a few simple steps, not an obstacle course.

Conclusions

Conference organisers and publishers have been running riot for years, reporting the results of their meetings with a concerning lack of discipline. It’s chaos. It has to stop.

What is needed is structure - in reporting, in accessibility, and in the most basic adaptable technology. Our proposals seek to reduce the number of steps users of conference proceedings must navigate (aligned with the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable data principles) (6).

In theory, this could be what is sometimes known as a ‘win win’. Not the linguistic shrug of a double negative but an actual honest to goodness opportunity. Delegates’ work becomes easier to find; users can reach it without dread; and - if we allow ourselves a reckless moment of optimism - conference organisers may even enjoy a small golden age, marked by rising usage and a corresponding fall in irate emails about access.

All that’s required is that organisers and publishers listen and change. A modest ask, really. Still, it’s in that tiny pause - between hearing and doing - that one senses how life, or at least conference infrastructure, might yet begin anew.

Notes: we initially submitted this to the journal of clin ep as a commentary. They proposed re-submission as a letter to the editor and said we should ‘remove the emotion’. We think some things, like this, are worthy of emotion – because you need to care enough, to attempt to bring about change. So we publish here instead – emotion intact.

Please cite this as: Cooper & Premji (2026) Reforming the presentation of conference proceedings: a plea to end the madness. Accessed via: https://www.thesearcheruk.com/blog/reforming-the-presentation-of-conference-proceedings-a-plea-to-end-the-madness (Date). DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.18593615

References

1. Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Featherstone R, Littlewood A, Metzendorf M-I, et al. Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies [last updated September 2024]. In: Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 65Available from cochrane.org/handbook Cochrane 2024).

2. Cooper C, Snowsill T, Worsley C, Prowse A, O'Mara-Eves A, Greenwood H, et al. Handsearching had best recall but poor efficiency when exporting to a bibliographic tool: case study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2020;12339-48

3. European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Past Congresses Resources - Heart Failure Congress.2026. URL: https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-Events/Heart-Failure/Congress-resources (Accessed 9 Jan 2026).

4. ISPOR. ISPOR Presentations Database.2025. URL: https://www.ispor.org/heor-resources/presentations-database/search (Accessed 9 Jan 2026).

5. ASH. Blood Volume 146, Issue Seupplment 1, Noveber 3 2025,.2025. URL: https://ashpublications.org/blood/issue/146/Supplement%201 (Accessed 9 Jan 2026).

6. Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 2016;3(1): 160018

Table 1: Two vignettes on the experience of handsearching

Two vignettes on the experience of handsearching

Cochrane define handsearching as: ‘a manual page-by-page examination of the entire contents of a journal issue or conference proceedings to identify all eligible reports of trials’ (1). This is meant literally: page-by-page, abstract-by-abstract. Now let’s consider that in practice with Figure 1 open.

Searching ASH

ASH reports its abstracts in the journal Blood. Once the distracting advertisement pop-ups have been dismissed, a searcher navigates to a specific drop-down where the meetings and late breaking abstracts are listed in order under a drop-down menu.

The abstracts report by title and there is no way (as there is in a bibliographic database) to toggle and include abstracts within page view. To view the abstract, the searcher must click through on ‘view article’, which takes you to a page specific to the abstract, where a decision can be made, in the fullness of abstract detail, to include or exclude.

There are literally thousands of abstracts to review and, as above, a handsearch as defined by Cochrane is a manual review of each abstract. This means either screening cautiously on title or clicking through thousands of abstracts.

The struggle does not end here. If one finds an eligible abstract, the abstract needs to be downloaded to a bibliographic tool. Ostensibly simple: click tools, click cite, select bib tool and download.

ASH now passes both citation and abstract – many conferences pass only a citation (even though they offer citation OR citation + abstract), so the abstract must be manually copied each time, and added.

The point here though is that a searcher is having to manually select individual abstracts and download them individually. It is >5 clicks to download rather than selecting a batch and bulk downloading in one step.

International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis

It takes some digging, but ISTH list their abstracts also via a dropdown menu, all actively linked to the journal ‘Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis’.

ISTH report via PDF documents. This can make the process of handsearching easier as one scrolls through abstract-by-abstract (perhaps using keyword highlighting) but on finding an eligible abstract the only option to export to a bibliographic tool is by copy and pasting from the PDF. It is messy and imperfect, with multiple fields needing to be populated. The formatting enrages the researchers screening too.